From time to time I get telephone calls from Mrs Mandrel, whom, in the midst of a car boot sale has found something that ‘might interest me’. When I visit such events I usually discover rust-riddled-reamers and chucks so bell mouthed you could ring them! My wife often has more luck. One day, I encouraged her to search me out a cheap aneroid barometer to calibrate an electronic barometer I was testing. She rang that day with a tale of various ‘pressure meters’, I said go for it, and it turned out that she did rather well. In a series of tins and boxes she presented me with two working barometers, a third with no needle and a whole host of barometer spares, all virtually given away with that wonderful British sentiment ‘they would go to someone who wants them’. There was also the, very grubby, internal mechanism from a large pressure gauge, probably 4” in diameter. Initially I thought this may have been from a full size steam engine, but it appears to read only to about 20psi, so who knows what its original purpose was?

Along with all these rather tatty but useful bits and pieces, was another gauge that had been polished up and mounted on a stand made from a piece of hardwood. Advised by a bystander that it was rather old and a good deal, my wife parted with £5 for this object.

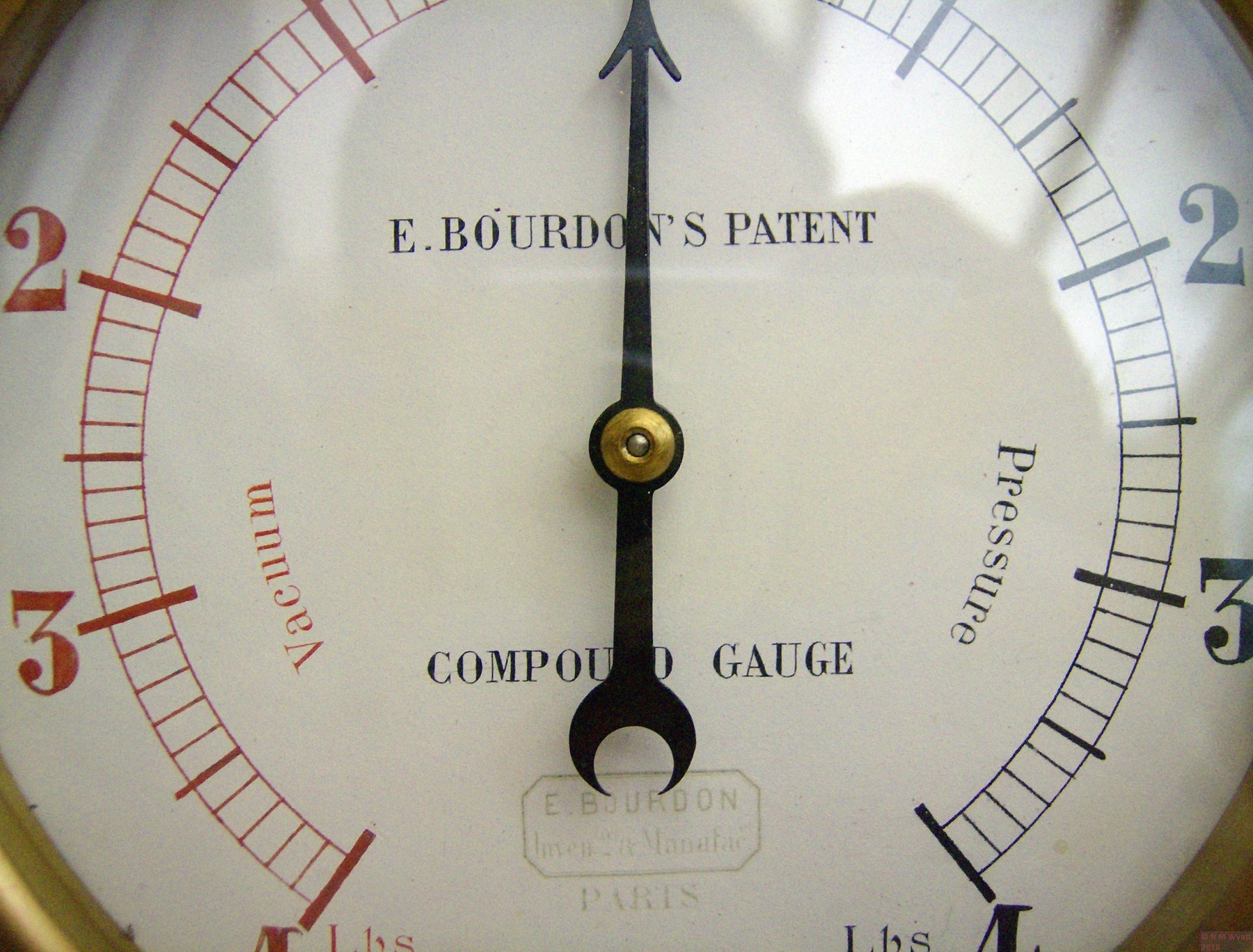

It took me a double-take to be sure exactly what this object was. At a glance it was a large pressure gauge, on inspection it was compound gauge, measuring vacuum and pressure. Better still, it was a genuine “Bourdon Compound Gauge” – a fine instrument and possibly one made in the days of Monsieur Bourdon himself!

Eugene Bourdon's Patent Compound Gauge

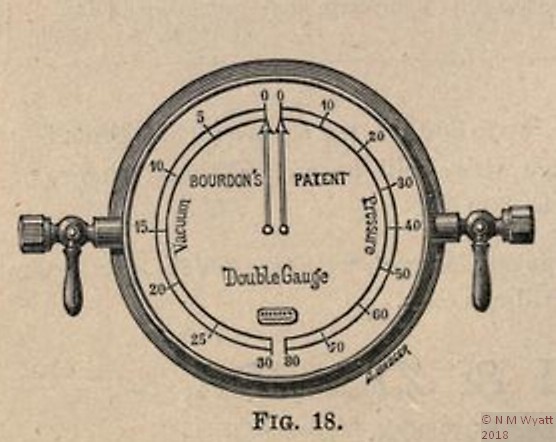

Patented by Eugene Bourdon in 1849, the Bourdon Gauge is a familiar instrument to model engineers, most usually encountered as a means of measuring steam or air pressure. The working principle is simple – a curved pipe, usually of a thin, springy material such as hard brass or beryllium copper, unrolls slightly when pressurised (like the feathered toys found in Christmas crackers!) This movement is amplified by a rod and lever, and, with better quality gauges, passed to the indicator needle via a pinion and a sector of a gear. Bourdon gauges can also be arranged to read vacuum relative to ambient pressure, and, if the mid point of the scale is carefully chosen pressures above or below ambient may be measured.

Such a gauge, measuring both pressure and vacuum, is a ‘compound gauge’, and mine was an example of this, reading +/- 4 pounds (presumably per square inch), subdivided to tenths of an inch. 4 psi is 276 millibars or rather more than a quarter of an atmosphere.

The gauge is housed in a heavy, circular brass case, 5” in diameter and 2” deep with a flange 6 1/2” across. A bezel holds in place a glass that is clear and without blemishes, but lightly rippled, suggesting that it is original old glass predating modern float glass. At the bottom of the circular case is a large thread, on which a nutted union fits, this appears to be original and contains a rather worn fabric washer. The union joins to a bent brass tube with a soft-soldered brass piece on the end, which appears to have provided a spigot for attaching a rubber tube.

The dial of the gauge is beautifully hand-figured in red (vacuum) and black (pressure) ink. In impeccable hand lettering the dial is also marked “E. BOURDON’S PATENT COMPOUND GAUGE”. Beneath this is stamped the maker’s mark “E. BOURDON Inventor & Manufac.or PARIS”. This mark is repeated, with only minor differences as a deep stamping in the rim of the brass case. Adjacent to this mark is the stamped number 10, probably not a serial number, it may relate to a calibration record. The case itself, and its bezel, appear to have been turned from brass castings. The finish is either very fine turned or finished with emery – not a polished appearance.

Markings on the dial

On removing the gauge from its plinth a black steel backplate is revealed (which may have been repainted), along with the serial number 3614 stamped into the case. On removing the backplate the mechanism is revealed, together with, scratched into the back of the dial, the serial number 3614 once again and the initials AM. These are both in a bold and, to my eye, continental hand. There are also the figures 11 and 2 marked in a more casual hand. The mechanism itself is pinned and screwed together. Interestingly the lever is made adjustable in length. Presumably the screw allowed calibration to be carried out before the two parts of the lever were finally pinned together. Aside from steel pivots and the copper(?) Bourdon Tube itself, all parts are brass and not highly finished.

Inside the case

An interesting touch that can just be seen in the photograph is that the end teeth of the gear sector that turns the pinion have been bent inwards. A crude but effective way of ensuring that over or under pressure can’t run the pinion off the end of the sector.

My limited lungpower can drop the vacuum to the full 4”, but only raise 1” of pressure. The reading appears accurate compared to a good quality but less sensitive modern gauge. It only reads correctly when the gauge is vertical; lying it down introduces an error of 1/2” of pressure, which illustrates how sensitive an instrument it is. Whilst ideal for demonstrating that a model engine can run on the merest whiff of air pressure, the gauge is far too sensitive for use on a working steam engine. It seems to me that this is a laboratory instrument of some class. Perhaps it was rescued from a school or university laboratory during the days when any useful, educational or interesting equipment was liable to end up in a skip, and mounted on its wooden plinth by appreciative hands?

I was surprised by how difficult it is to find out more about Monsieur E. Bourdon and his invention, despite the fact that there are now millions in use across the globe. Eventually, I was directed to a 1887 Negretti and Zambra catalogue which showed the same maker's stamp and embossing on the gauge.'Purchasers are desired to examine and compare M. Bourdon's Gauges. They will find the works to be constructed and finished like a watch, whilst the majority of imitations are put together ROUGH FROM THE CASTINGS, consequently liable to adhere and give erroneous indications'.

Bourdon's Patent Double Gauge in an 1887 catalogue

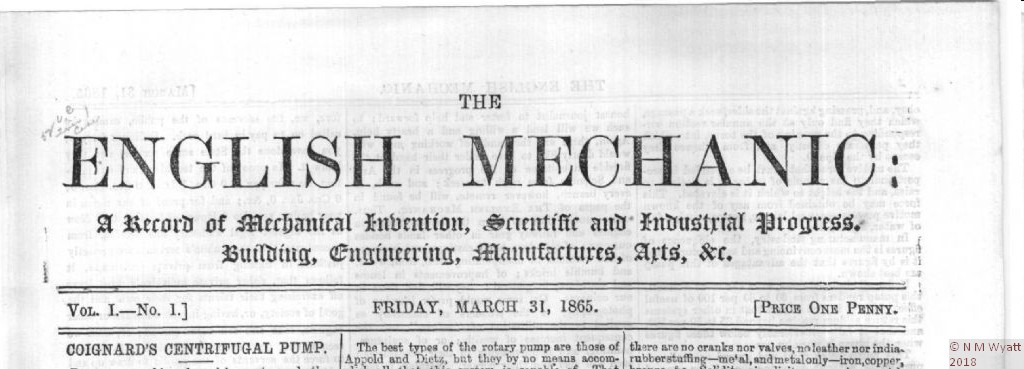

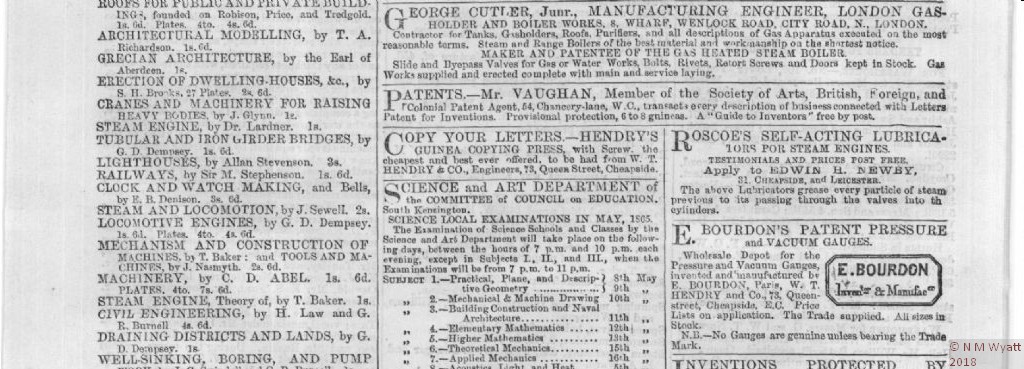

A second source gave images showing the mark in an 1865 issue of The English Mechanic. It seems that the gauge would have come out of M. Bourdon's workshop some time between 1850 and 1890, if you can help with dating from the serial number, please get in touch.

The English Mechanic, March 31 1865

The Maker's Mark in the text...

... and on the case

I contacted the Science Museum, whose expert stated he can's remember seeing one in such good condition. They already hold another gauge presented by M. Bourdon himself in their Motive Power collection (inv. 1877-450).

So, it seems this gauge is rather special but best of all at over 150 years old, it still has a job of work to do from time to time. I hope this article makes it easier for anyone else with a similar gauge to find out its history.